Can money buy better health? Not directly, maybe—yet research findings suggest that Americans with the highest income rates are also more likely to report better health status and achieve a longer life expectancy compared to low-income families.

How pronounced is the difference in health outcomes between the ultra-wealthy and the rest of us? What factors contribute to these class-based health disparities? We dug into data pulled from numerous sources to find out.

Health Equity and Income Inequality

An article by U.S. News & World Report didn’t mince words when it announced, “More money equals better health care and longer life.”

Numerous factors come into play when you look at health disparities as a social issue. Yet over and over again, experts have pointed to income inequality as the single largest factor.

According to U.S. News & World Report, “America’s poor — of any race or ethnicity — are sicker than well-off Americans.” This reality led the publication to call income inequality “the deepest and most persistent divide” in health disparities. An expert quoted in the U.S. News article, Professor Ichiro Kawachi of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, went so far as to say that “unequal economic opportunities, unequal education, and despair” constitute “the root” of racial disparities in health care.

The inequality in health that persists in America encompasses three distinct but related issues, according to U.S. News.

Disparities in Health Outcomes and Increased Rates of Poor Health

Rates of several health issues are significantly more pronounced among some populations than others. Often, these groups that are disproportionally afflicted by health problems include low-income families, as well as racial and ethnic minority populations.

As a health policy brief published by Health Affairs reported, low-income families have higher obesity rates, diabetes rates, stroke rates, heart disease rates and rates of other chronic diseases.

Income inequality also extends to higher rates of physical limitation among low-income people. Naturally, these physical limitations don’t help matters among those with the lowest incomes.

Patients with low incomes have more trouble affording the assistive devices that would allow them to more easily go about their lives. They may not be able to hire outside help for tasks they struggle to perform on their own. These physical limitations may further affect their incomes by reducing employment opportunities. Additionally, physical limitations may interfere with the goal of improving health through exercise.

From all angles, the physical limitations that are more prevalent among the low-income population only exacerbate the problems that already arise out of the relationship between household income and health status.

Disparities in Health Care

Compounding the problems of disparities in health itself are inequalities in the quality of medical care patients in these affected populations receive.

Those who already suffer from poor health need quality health care the most to manage their conditions and reduce the likelihood of complications. Yet, in America, these patients are also the ones least likely to get the health care they need. Numerous explanations for disparities in health care have been proposed, including the lack of financial access to care among low-income families and what U.S. news referred to as “implicit bias” within the health care system.

Inequality in Health Insurance

In America, health care is prohibitively expensive without health insurance. As such, not having adequate health can severely impact one’s ability to get the medical care they need.

Unfortunately, access to health insurance, too, is affected by income inequality. Too many Americans are either uninsured or underinsured.

Low-Income and Uninsured

For the population of Americans that doesn’t have health insurance at all, financial concerns are the most common cause.

The high cost of health insurance is a major reason why 27.5 million people remained uninsured as of 2021, according to the nonprofit organization KFF (formerly the Kaiser Family Foundation). Nearly 70% of uninsured Americans report the unaffordability of insurance as being the biggest barrier to getting insured, KFF reported.

Who are these tens of millions of uninsured Americans? Often, they are workers who either don’t qualify for or can’t afford their share of employer-sponsored insurance plans. More than 70% of the (nonelderly) uninsured population had at least one full-time worker in the household, KFF reported.

Here, too, racial and ethnic disparities are apparent. While people of color accounted for approximately 45% of the U.S. population, they made up more than 61% of the uninsured population in 2021, according to KFF.

Immigrants, too, made up a disproportionate rate of the uninsured population. Nearly 29% of immigrants who have lived in the United States for less than five years reported having no health insurance in 2021. So did nearly 35% of immigrants who have lived in America longer than five years—indicating that the problem gets worse, not better, the longer an immigrant has called the U.S. home.

Unsurprisingly, most people who are uninsured fit into lower-income groups—or, at least, groups outside of the 1% or 5% of top earners.

For those with high household income rates, like the 1%, the costs of health insurance coverage are comparably minimal. Their well-paying jobs are more likely to include good (that is, inexpensive to the insured) health insurance coverage. Even if households in the top 1% of earners don’t have employer-sponsored health insurance, they can afford to purchase coverage on their own.

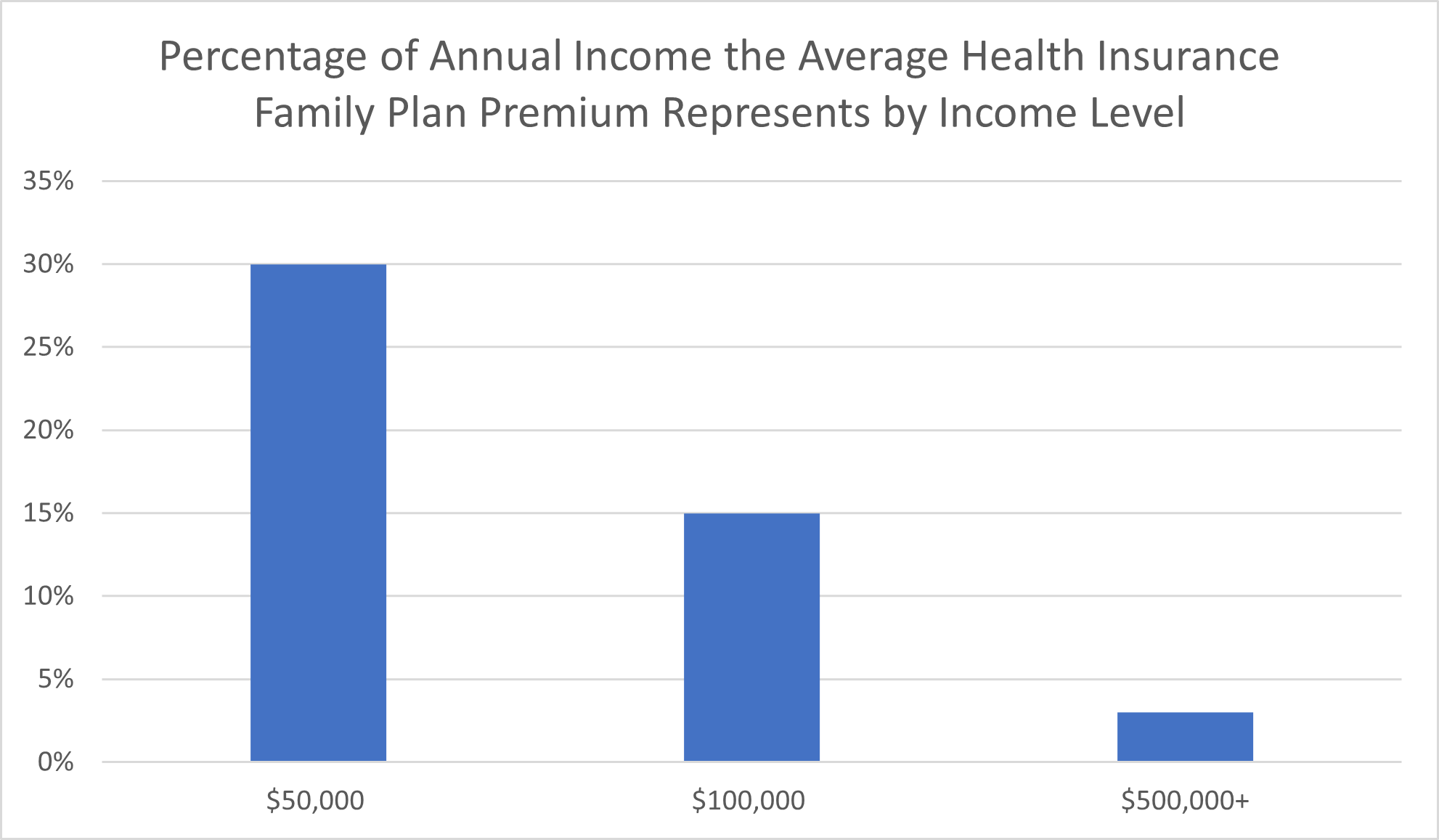

An October 2022 article by private online health insurance marketplace eHealth listed the average monthly health insurance premium cost as $484 for an individual or $1,230 for a family. What’s $5,808 per year—or even $14,760 per year—when you make $500,000 or more annually? We’re talking, at this point, of individual insurance premiums that amount to barely over 1% of high-income households’ annual earnings. Even family coverage is under 3% of the yearly earnings that, according to most income thresholds, represent the minimum income rate required to be part of the 1% nationwide.

Of course, most people aren’t in these exceptionally high-income groups. For Americans in more modest household income groups—who don’t have good employer-sponsored coverage—health insurance premiums are among their biggest regular expenses. The family health insurance premium eHealth listed in October 2022 amounts to more than 93% of the $1,320 average monthly rent amount Statista reported for a two-bedroom apartment in February 2023. Americans who don’t qualify for subsidies may well be paying almost as much each month for health insurance as they are for housing. Keep in mind, too, that this cost refers to the premiums policyholders pay for the privilege of having health insurance, not even counting the deductibles, copayments and co-insurance payments they have to pay to actually use their insurance.

What this data on uninsured Americans from KFF indicates is that limitations on access to health care are particularly pronounced among low-income Americans—yet these obstacles aren’t exclusively the problems of the households with the lowest incomes.

For most uninsured families, KFF reported, household income amounted to less than four times the federal poverty level; nearly half of these households reported a family income less than twice the federal poverty level. In 2021, a family of four could still be within 200% of the federal poverty level ($26,500) while earning upwards of $50,000. A family of four that earns $100,000 per year is still within 400% of the federal poverty level.

After all, the average private health insurance premium for a family plan amounts to nearly 30% of household income for families earning $50,000 per year. Even for those families earning income right at the six-figure mark, a private family insurance plan eats up nearly 15% of annual earnings before taxes.

Keep in mind that this data pertains only to Americans with no insurance. It’s not even counting the millions of Americans who, STAT reported, are insured on paper but whose health insurance plans have such high deductibles or cost-sharing obligations that the policyholder can’t afford to use their coverage.

Health Spending by Income Level

You can’t spend money you don’t have, even on critical healthcare tests and treatments. While the 1% can afford a much higher rate of health care spending, this leaves lower-income Americans with two options: go into debt or go without.

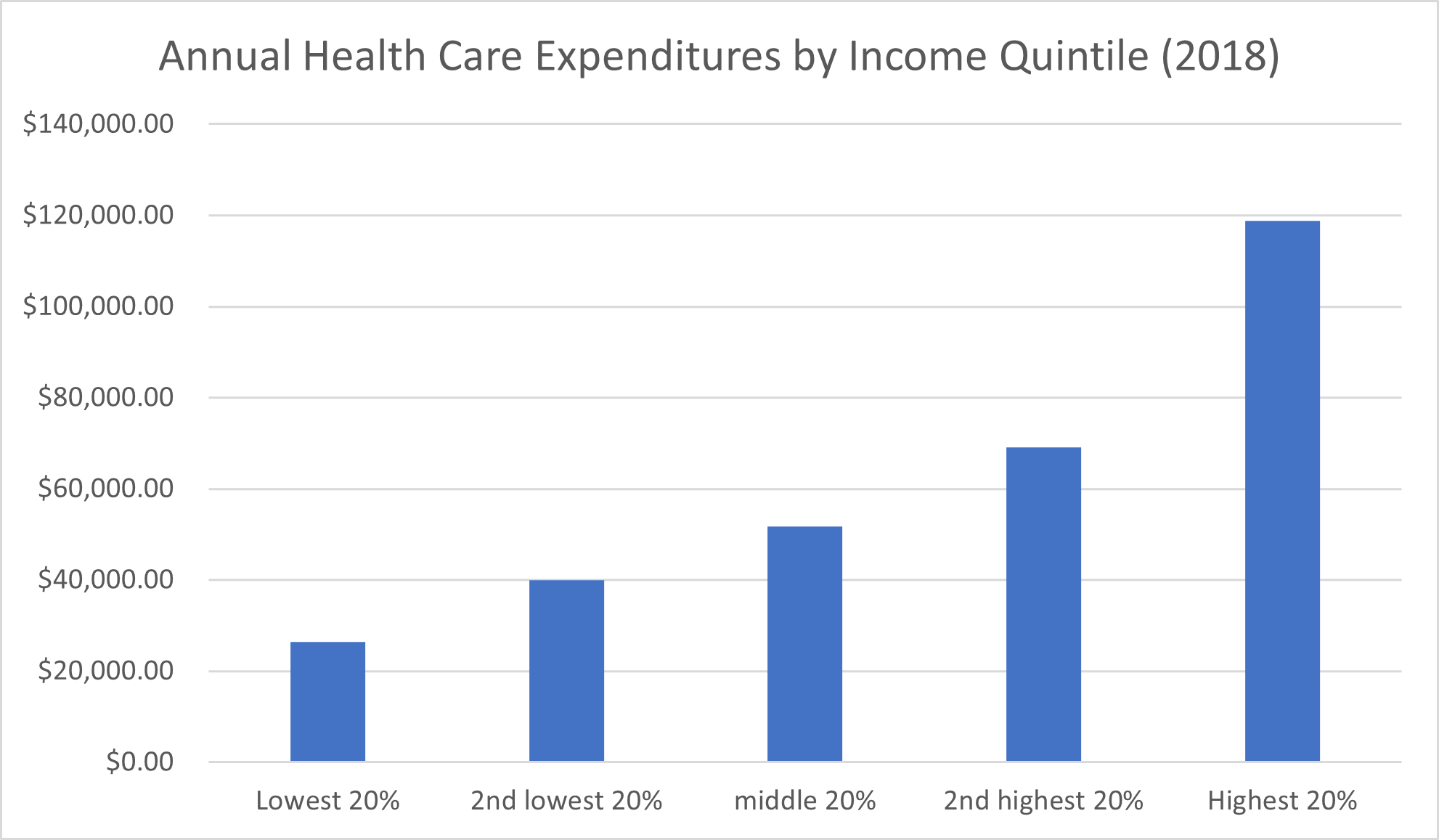

In a 2018 report on health care spending, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) presented data concerning health care spending by income quintiles.

Among households in the lowest income quintile—that is, the lowest 20% of earners—total health care expenditures in 2018 amounted to $26,398.71, the BLS reported. (Keep in mind that total health care expenditures aren’t the same as how much the household is spending because this figure may include health care spending that is covered by private insurance companies, Medicare, Medicaid, and government or nonprofit health programs.)

The next lowest income quintile reported an average annual health care expenditure of $39,967.97. For the middle 20% of earners, the average health care spending in 2018 amounted to $51,728.65. The quintile that made up the second-highest income group reported average health expenditures of $69,130.70. Finally, the top 20% of Americans with the highest income reported average health care spending of $118,780.66 in 2018.

There’s a clear progression in average health care spending amounts across income groups, but it’s not necessarily a good thing that lower-income households spend less on health care. For one thing, these expenditures include not only the individual’s share of health care spending but also overall spending on health care services by payers like private health insurance companies, Medicare, and Medicaid.

By share of annual expenditures—the amount of money out of their total spending that households allocate to health care costs—the quintile that represents the second lowest-income group paid the highest share of annual health care expenditures: 10%. The quintile representing households with the lowest incomes paid the next highest share of annual health care expenditures, at 9.4%, followed by the middle class (or at least, middle quintile) paying a share of 9%. Earners in the second-highest quintile paid an 8.5% share of annual health care expenditures, and the quintile representing households with the highest income paid the lowest share of annual expenditures by far, at 6.6%.

Paying for Medical Costs: The 1% vs. Everyone Else

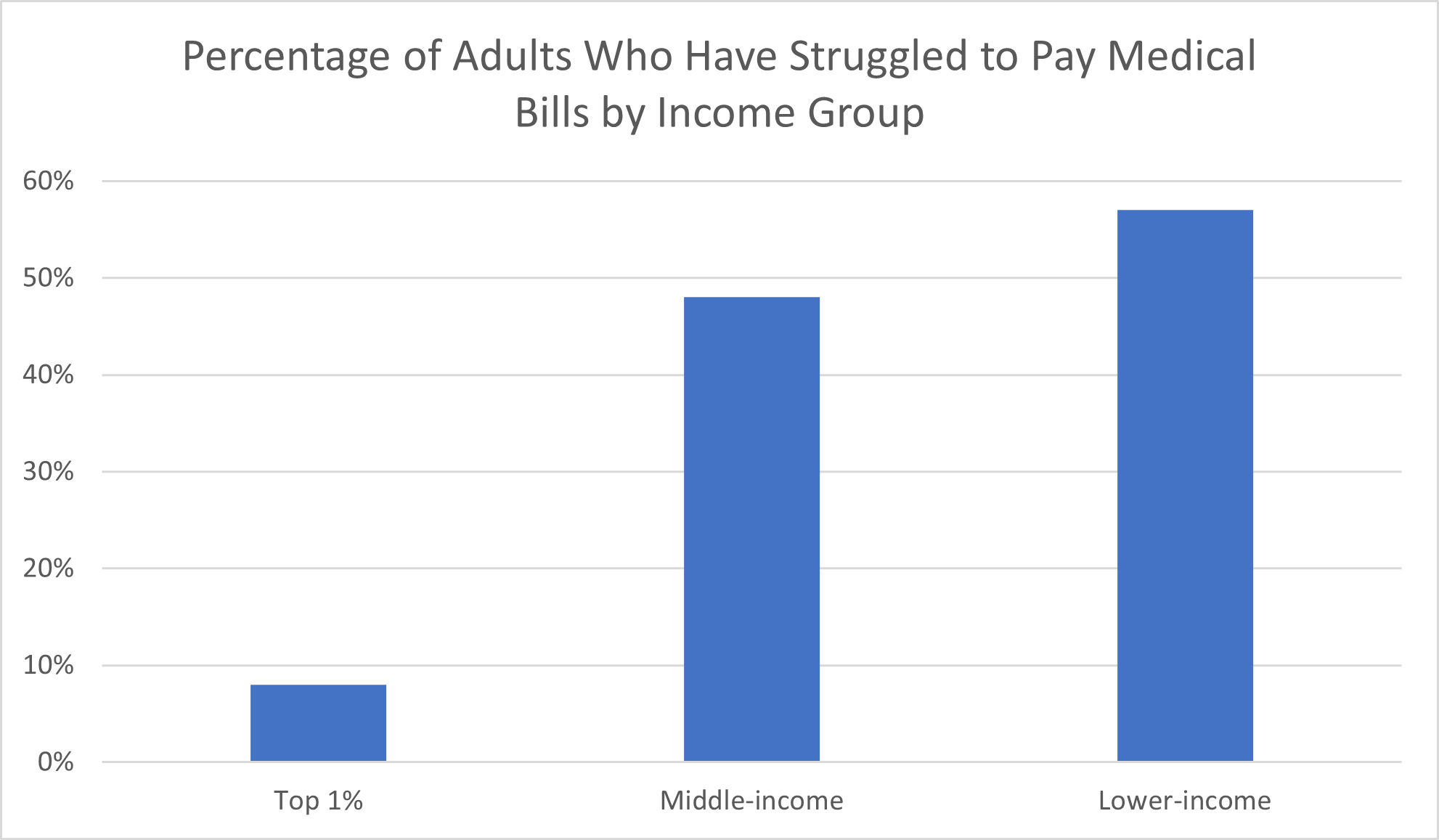

You probably don’t need data to back up the assertion that the lives of the top 1% are very different than those of average Americans. Still, the January 2020 findings published by researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (in collaboration with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and NPR) quantified and elaborated on the “dramatically different life experiences” the 1% have compared to, well, everyone else.

Among the adults with the 1% highest income rates, just 8% reported having “serious problems” paying medical bills, prescription drug costs or dental bills “in the past few years,” the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health reported. To put that in perspective, nearly half (48%) of survey respondents classified as middle-income had trouble paying for medical care. Among lower-income adults, the percentage that had experienced problems paying for medical care climbed to 57%.

For the purposes of this poll, the 1% encompassed adults with household incomes of at least $500,000 per year. The other income thresholds are as follows:

- Higher-income: $100,000-$499,999 per year

- Middle-income: $35,000-$99,999 per year

- Lower-income: $34,999 or less per year

Unexpected medical emergencies, in particular, pose serious problems for income groups outside the 1%—and the lower their income level, the more these groups feel the consequences.

While a third of middle-class earners reported that they would “struggle” to pay an unexpected expense of $1,000, two-thirds of lower-income working-age adults would struggle. Only 4% of the 1% income group would struggle to afford this surprise expense.

When you consider that an unplanned surgery, hospitalization or even an emergency room visit could cost much more than $1,000, it drives home just how precariously the budgets and savings of lower-income groups are balanced in comparison to higher-income families. $1,000 of medical expenses in America may not add up to much care. Even a relatively routine procedure or comparably minor accident could be enough to incur this medical debt.

Income Inequality and Life Expectancy

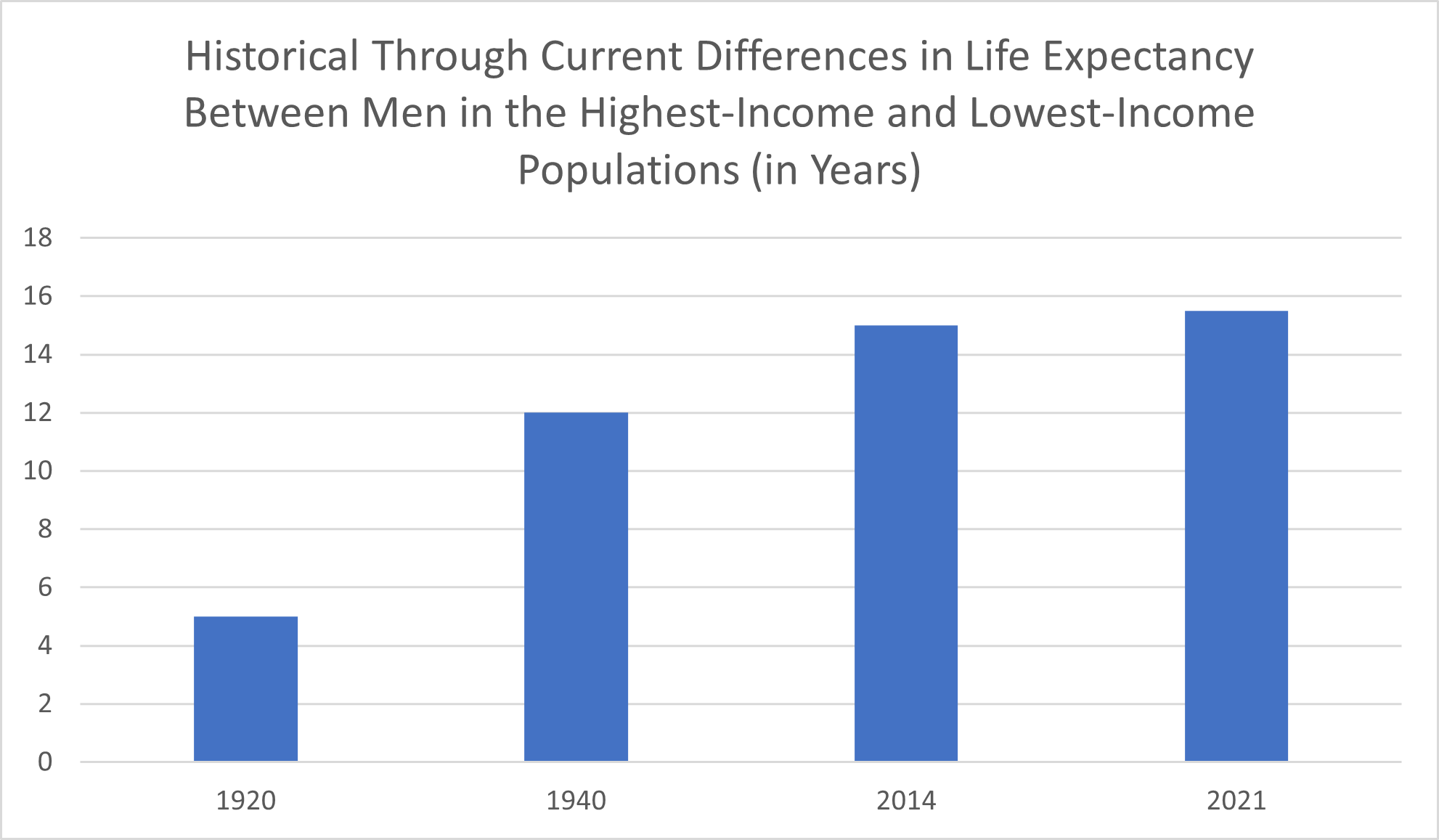

One particularly stark example of how income inequality affects health is differences in life expectancy. The poor literally die younger than the rich.

The significant differences in life expectancy across income levels are longstanding, but they’re growing more pronounced. According to U.S. News & World Report, this difference amounted to five years for men born in 1920 but had already increased to 12 years for men born in 1940.

By 2014, the differences in life expectancy between the richest men and the poorest men in the United States amounted to 15 years, The Equality of Opportunity Project reported. In 2021, Northwestern University researchers found that, at least in California, the gap had widened still more under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, to 15.5 years.

It isn’t only the distinction between life expectancy by household income that’s alarming. It’s also the progress (or lack thereof) toward a longer life expectancy that people of different family income levels are making. As Health Affairs noted, when the rich have seen positive increases in life expectancy in recent years, poor families have seen “no gains” at all.

How significant a factor is household income in determining life expectancy? Family income level can affect a person’s average lifespan as much as, or potentially even more than, the lifestyle factors that have been most extensively researched and proven to be detrimental to health status.

The 2018 Health Affairs article reported that the 10-year life expectancy difference between women (who have a longer life expectancy anyway) in the top 1% of income compared to the bottom 1% is “an effect equivalent to that of a lifetime of smoking.”

Even dying costs more among people of lower socioeconomic classes in the United States. “Medicare beneficiaries who die in low-income areas have higher end-of-life costs,” researchers wrote in an article published in the Royal Society of Medicine—even though these families are the ones least able to afford this added financial burden.

The theoretical looming threat of an early grave isn’t the only shadow income inequality casts upon poor families. Health disparities arising out of income inequality are affecting the quality of life of tens of millions of Americans right now. In turn, this poor health compromises any ability these workers may have to increase their income and escape the cycle of poor health and low income.

The Lasting Health Effects of Growing Up in Low-Income Households

Suppose you grow up in poverty, but you beat the odds, get an education and end up increasing income well beyond what your family of origin had. Can you escape the health consequences of childhood income inequality? What researchers found, according to the independent Center for American Progress, is that disparities across childcare, economic security, housing and, yes, health care aren’t so easily shaken off. These disparities “affect babies for life,” the report disclosed.

A major reason the effects of being raised in lower-income households can affect children long after increasing income and economic security is that children’s earliest experiences “have strong impacts on brain development,” the Center for American Progress reported. Drawing on earlier research into human development, this report digs into the foundations needed for good health and the processes by which exposures to stress and insecurity in lower-income households affect health status.

Babies born into the highest income levels enjoy the benefits of wealth from the start, even if they aren’t aware of their good fortune. They get the care they need from (or even before) birth. In their financially stable and secure environment, the stress to which they are exposed is less compared to what babies born into poor families experience. Against this backdrop, a baby’s brain is better able to develop in typical, healthy ways.

Among children in families with the lowest incomes, stressful experiences, including neglect, can actually disrupt the development of the baby’s brain and other biological systems, the Center for American Progress reported. This is one explanation why children raised in families with the lowest incomes have a higher risk of developing a variety of chronic health issues later in life. These conditions include diabetes, heart disease, anxiety, depression, and substance abuse disorders, the report concluded.

Exploring the Causes of Health Inequity Across Income Groups

Now that we’ve examined how the health of the top 1% and other top earners compare to the average American, the question that naturally comes to mind is: why?

There are no simple answers. Instead, there are complex relationships between interconnecting factors. As the U.S. News & World Report article referenced above noted, it’s hard to say whether health inequality is a cause or an effect—or, to some degree, both—in relation to problems like income inequality, education inequality, racial inequality, gender inequality and housing and geographical inequality.

That is, are high-income families healthier than low-income families because of the medical care they receive? Or do environmental and lifestyle factors that aren’t directly related to health spending play bigger roles in the differences in health outcomes among low-income families compared to middle-class families and higher-income households?

There’s a lot to unpack here. On the one hand, the households with the highest income can certainly afford medical care more readily than low-income families. They can undergo regular checkups and routine screenings that a patient with high insurance copays or no insurance at all can’t afford.

When a medical problem arises, higher-income patients are better able to get medical care right away instead of taking the “wait and see” approach to determine whether they really need to see a doctor or whether the issue goes away on its own. This puts the lower-income patient who avoids timely medical intervention at a greater risk of complications or progressions of the condition—which, in turn, can be even more expensive.

It’s worth noting, too, that the obstacles to getting the care one needs aren’t always directly related to health spending. Time is money, after all. Taking unpaid time off from work to see a doctor for a wellness visit or recover from an illness isn’t always feasible, especially for working-age adults in low-income groups. This time off could mean the difference between being able to put food on the table or gas in the car. For some workers, doing so could even put them out of a job.

Money may not (or perhaps it may) be able to buy health directly, but it can buy a lot of the things that are closely tied to excellent health.

Working adults with higher incomes are more likely than those with the lowest incomes to have the leisure time and resources to focus on their fitness. For example, a single parent who works two jobs to make ends meet likely doesn’t have the time to devote to going to the gym multiple days a week, the cost of a gym membership notwithstanding—and the cost of childcare only adds to the expense.

That isn’t to say a high-income worker can always get the time off from work that they need to focus on their fitness. The work many high-income workers, such as doctors, lawyers, and senior managers, do is high-pressure.

However, you don’t need to have the kind of job that allows you to take an afternoon off because you feel like going golfing for your income level to impact the feasibility of prioritizing your health and fitness. Having a higher income level may allow you to outsource other tasks that take up your time—like cooking, cleaning, yard work, and childcare—which frees you up for exercise and other activities that are good for your physical and mental well-being.

Having the money to eat healthily is another benefit households with a high income enjoy. Purchasing a healthy variety of high-quality, nutritious foods costs more than buying larger quantities of less nutritious food. Preparing fresh, healthy foods also tends to take more time.

Even if the adults in a low-income household make a consistent effort to provide a healthy lifestyle for their family and use the bulk of their resources to ensure adequate exercise and nutrition, they may be at a geographical disadvantage. The facilities that produce toxic pollutants that contaminate the air we breathe are disproportionately located in the areas with the lowest incomes and, often, in “low-income communities of color,” Urban Institute’s Housing Matters initiative reported in 2022.

Teasing out whether individual poor health outcomes of patients living in low-income households result from lifestyle factors, toxic environmental exposures, complications from prior illnesses, or other factors is complicated, if not impossible. However, looking at larger sets of data pertaining to health outcomes and income inequality makes it clear that some relationship exists between the various factors at play in health outcomes and social issues.

Income Inequality and the Future of Health Care

What’s the importance of understanding the relationship between income inequality and health if we can’t use that knowledge to shape the future of health care?

Health care in America is too often viewed as a zero-sum game, with not enough care providers, medications, and other resources to go around. Yet it’s clear that the prevalence of chronic diseases that are so over-represented among the low-income population is unfavorable not only for individual patients but for the health care system as a whole.

The economic and opportunity costs of preventable chronic diseases drain resources from the health care system and contribute a great deal to health care spending. However, the associated medical interventions don’t provide better health. Rather, they aim to manage and mitigate long-term problems that will, almost inevitably, get worse over time.

It’s a great thing when individuals prioritize their health by making healthy lifestyle choices and getting routine wellness checkups and screenings. However, the American health care system and the nation as a whole benefit when even the population with the poorest health outcomes makes significant gains in health status and average life expectancy.

Improving health and health care in America means making conscious efforts to bring the health of the lowest-income households in line with that of the highest-income households. There are numerous ways to approach this effort, including health outreach and education in low-income communities.

Health policy is among the most prominent approaches to improving health among households in poverty. Perhaps the most important health policy initiative in America in the last couple of decades was the adoption of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (Obamacare).

Although many found this law to be controversial at the time (and some Americans still do), as a health policy, it made an impact on numerous fronts. In the first 10 years since these health policy changes were enacted, the number of Americans without health insurance declined by 1.2 million, the Center for American Progress reported. Expanded Medicaid eligibility extended government health insurance to a significantly larger population of low-income households and especially to children. Certain provisions of the Affordable Care Act, like protecting patients with pre-existing conditions from discrimination by insurance companies and permitting young adults to stay on their parents’ health insurance policies longer, have achieved widespread popularity across the political spectrum.

As previous research has revealed, health equity isn’t a simple problem with a simple solution. As such, modern health legislation shouldn’t be developed in a vacuum. Policy analysts and politicians should craft policies that not only take into account the effects of income inequality on health outcomes but also the relationship between health and the numerous obstacles that lower-income households face that affect health outcomes and access to health care. Only by investigating all of the factors of importance in income inequality can experts develop policies and laws that can begin untangling and addressing this complex issue.