Today, the credit card industry is a major player in the economy. Credit scores, the interest paid on credit card balances, and credit card debt all significantly impact consumer finances. On the industry side, credit card revenues and profitability on both the parts of issuers and processing networks express the financial health of the industry. By dollar value, more than a third of all transactions completed in the United States in 2021 involved credit card payments, consulting firm McKinsey & Company reported.

Credit cards didn’t always hold this prominent place in the United States economy. In fact, a century ago, credit cards didn’t even exist, and the first plastic credit card was introduced only 64 years ago.

How did the credit card industry grow to occupy such a critical place in the finance and insurance industry and the economy as a whole? In this deep dive into the growth of the United States credit card industry, we’ll explore the current state of the credit card industry and historical data that, together, paint the picture of how the modern credit card industry in America came to be.

A Brief Credit Card Industry Overview

Before we get into the history of the credit card industry and how this hundred-billion-dollar industry has grown over time, let’s take a moment to go over how the credit card industry works today. Understanding the parties involved in a credit card transaction and how the different entities that are part of the credit card industry make money is important for grasping the growth of this market over time.

Understanding Credit Card Issuers and Networks

Let’s start with the credit card business. Besides the cardholder and the vendor or merchant from which they’re making a purchase, two types of companies are involved in credit card usage.

Credit card issuers are financial institutions—in other words, the cardholder’s bank—that lend users the money they utilize in credit card transactions.

Credit card networks are the parties that facilitate and process credit card transactions.

The biggest credit card issuers in the United States today include Chase, Capital One, Citi, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. The major credit card networks are Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover. In most cases, credit card issuers are distinct from credit card networks. However, both American Express and Discover act as both the credit card issuers and the credit card networks that process transactions.

Visa has historically held the largest market share of the credit card network, followed by MasterCard, American Express, and finally, Discover.

At one time, banks that issued consumer credit cards were required to choose between Visa and Mastercard networks when offering consumer loans in the form of credit cards. Changes to association bylaws now allow many issuers to offer credit cards from either of these networks. This ability is ideal for credit card issuers because, despite Visa and MasterCard networks having more traits in common than not, these networks do offer some different benefits, WalletHub reported. Being able to issue cards belonging to both networks can increase the bank’s appeal to potential customers for whom the benefits of cards from one network are more compelling than another.

The Basics of Credit Card Loans

What is credit, anyway? A line of credit is, basically, a revolving loan. Credit cards are a form—one of the most prevalent and pervasive forms—of consumer lending. When you make a purchase with credit card accounts, you’re using money that isn’t yours and that has to be paid back.

Cardholders are, in most cases, approved to use their credit card accounts up to a certain amount of money, called a credit limit. Credit card limits apply to regular transactions, or purchases for which the consumer pays with credit card payments. Other types of transactions, like balance transfers and cash advances, may have separate limits, as well as fees, interest rates, and other terms, that apply.

Like borrowers using other types of loans, credit card users have to pay back the money they borrow from the bank. Unless they pay off their balance in full at the end of the statement period, they also have to pay interest on their credit card spending.

How the Credit Card Industry Makes Money

Interest charges are one of the ways that credit card issuers make money. Credit card interest rates today are often high. Higher interest rates translate to more income for credit card issuers.

Credit card companies also make money through the fees they charge cardholders—including late fees, over-limit fees, and annual fees (if applicable)—and through the transaction processing fees they charge companies that accept credit card payments.

- Late fees: As the name suggests, late fees are assessed when a cardholder fails to pay their bill—at least the minimum amount due—on time. Late fees usually range between $15 and $35 and often depend on the balance you’re carrying on your credit card account.

This penalty for late payment is a one-time charge, but multiple late payments or missed payments can rack up more costly and serious consequences. - Over-limit fees: Most credit card issuers only agree to lend cardholders money up to a certain amount. If a transaction puts you over your credit limit, one of two things may occur. Your card may be declined, in which case you can’t use it to make a payment. Alternatively—and only if you opted to allow the credit card companies to process transactions that put you over your credit limit—the transaction may go through, but you will be charged over-limit fees.

According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a federal government agency created to protect consumers from deceptive and unfair operations of banks and financial institutions, cardholders can be charged up to $25 for their first over-limit purchase. If a second over-limit purchase occurs within six months, consumers may be charged fees of up to $35. Credit card companies cannot, however, charge customers an over-limit fee larger than the amount by which they exceeded their credit limit. - Annual fees: Some credit card issuers charge cardholders annual fees for the privilege of having access to their credit card loans.

There are plenty of credit cards that don’t charge annual fees. One reason cardholders may choose to pay annual fees for credit card accounts is that the card provides benefits and rewards that other cards don’t offer and that are worth paying for. A consumer who is ineligible for cards that don’t charge annual fees due to poor credit history may have to pay an annual fee for a credit card bank to offer them even a basic card.

For a card that charges an annual fee, consumers will usually pay close to $100, if not more—and for cards that offer premium benefits, the annual fee can amount to several hundreds of dollars each year.

While the cardholder (the consumer) is the one responsible for paying late fees, over-limit fees, and annual fees based on how they use their credit card account, the vendor in a transaction has to pay transaction fees. Credit card transaction fees include payment processing, assessment and interchange fees.

A History of the Credit Card Industry

To appreciate how much the credit card industry has grown throughout the years, we need to go back to the beginning.

The credit card industry today is so large and so prevalent that it’s hard to imagine a time when credit cards didn’t exist. Yet the time when the credit card was invented wasn’t all that long ago.

The Earliest Credit Cards

The first credit card as we know it, the Diners Club Card, was invented in 1950, according to Forbes.

Precursors to the first credit card include the Metal Money plates issued by Western Union as early as 1918 and the 1930s’ charge plates. Charge plates were metal plates similar to dog tags that could only be used in limited situations—typically at individual retailers.

These metal plates that were put into use first by Western Union and later through the Charga-plate bookkeeping system allowed for limited charge payments. The next development after the introduction of charge plates was the Charg-It card. In 1946, John C. Biggins developed the Charg-It system. For the first time, a Charg-It card allowed customers to charge purchases from multiple merchants. Consumers with a Charg-It card could use the card to shop at multiple vendors within a two-square-block radius of Flatbush National Bank in Brooklyn, NY, Forbes reported.

The Diners Club card, introduced in 1950 by Frank McNamara and Ralph Schneider, wouldn’t impose the same limitations as the Charg-It card before it. The Diners Club Card allowed cardholders to charge to their account their meals at any of the more than two dozen participating restaurants across New York City and pay the bill later. The Diners Club card was the “first multipurpose charge card,” according to Diners Club International, and what most experts consider to be the first credit card. At the end of the statement term, Diners Club sent cardholders a bill that, at this time, needed to be paid off in full. It wasn’t until later that credit cards, including Diners Club cards, would allow customers to carry revolving balances from one statement term to another.

From early on, the first Diners Club cards were a hit with American consumers. Both the number of participating vendors and the number of Diners Club account holders saw rapid growth in the subsequent years. By 1951, the number of Diners Club cardholder accounts had climbed from just 200 to 42,000. Further, increasing acceptance of Diners Club as a form of payment in Mexico, Canada, the UK, and Cuba made the Diners Club card “the first internationally accepted charge card” by 1953, according to Diners Club International. Diners Club cards are still in use today.

The success of the Diners Club cards inspired competition. Other banks soon began issuing general purpose credit cards of their own. In 1958, both American Express and BankAmericard launched their own general purpose credit cards.

BankAmericard was distinct in multiple ways. This was the first credit card that allowed customers to carry a revolving balance from one month to the next. In that sense, it’s the first true credit card as we know it today, as opposed to charge cards, which have traditionally required cardholders to pay their balance in full after each statement period.

The BankAmericard credit cards also quickly gave rise to the first instances of credit card fraud. The cards were already activated when mailed out to the 60,000 customers who received them, Forbes reported. Bank Americard would later become Visa—the credit card network that, today, processes more transactions than any other network.

Another major name in credit cards would soon be launched. The Interbank Card Association, consisting of participating banks in California, released the Interbank Card in 1966. The Interbank Card Association would later change its name to MasterCard International.

The First Plastic Credit Cards

The first credit cards didn’t look much like the credit cards we carry around today. They were made of cardboard rather than paper and lacked the magnetic strip that would soon become popular—much less high-tech chips to read and touchless scanning functionalities.

In 1959, the first plastic credit card—an American Express card—appeared, Bankrate reported. Competitors would soon follow suit. Diners Club would replace its cardboard card with a plastic credit card in 1961.

The magnetic stripe that allowed for easy card-swiping at the point-of-sale terminal—back before there were chips to insert and tap-to-pay technology—was developed in the 1960s by an engineer named Forrest Parry. This technology, Forbes reported, became a standard part of credit cards in the United States by 1969.

Credit Card Users and Credit Card Accounts by the Numbers

Since these early days of credit card usage, consumer lending in the form of credit cards has exploded. One way to measure credit card industry growth over time is by the number of consumers who have embraced credit cards as payment methods through the years.

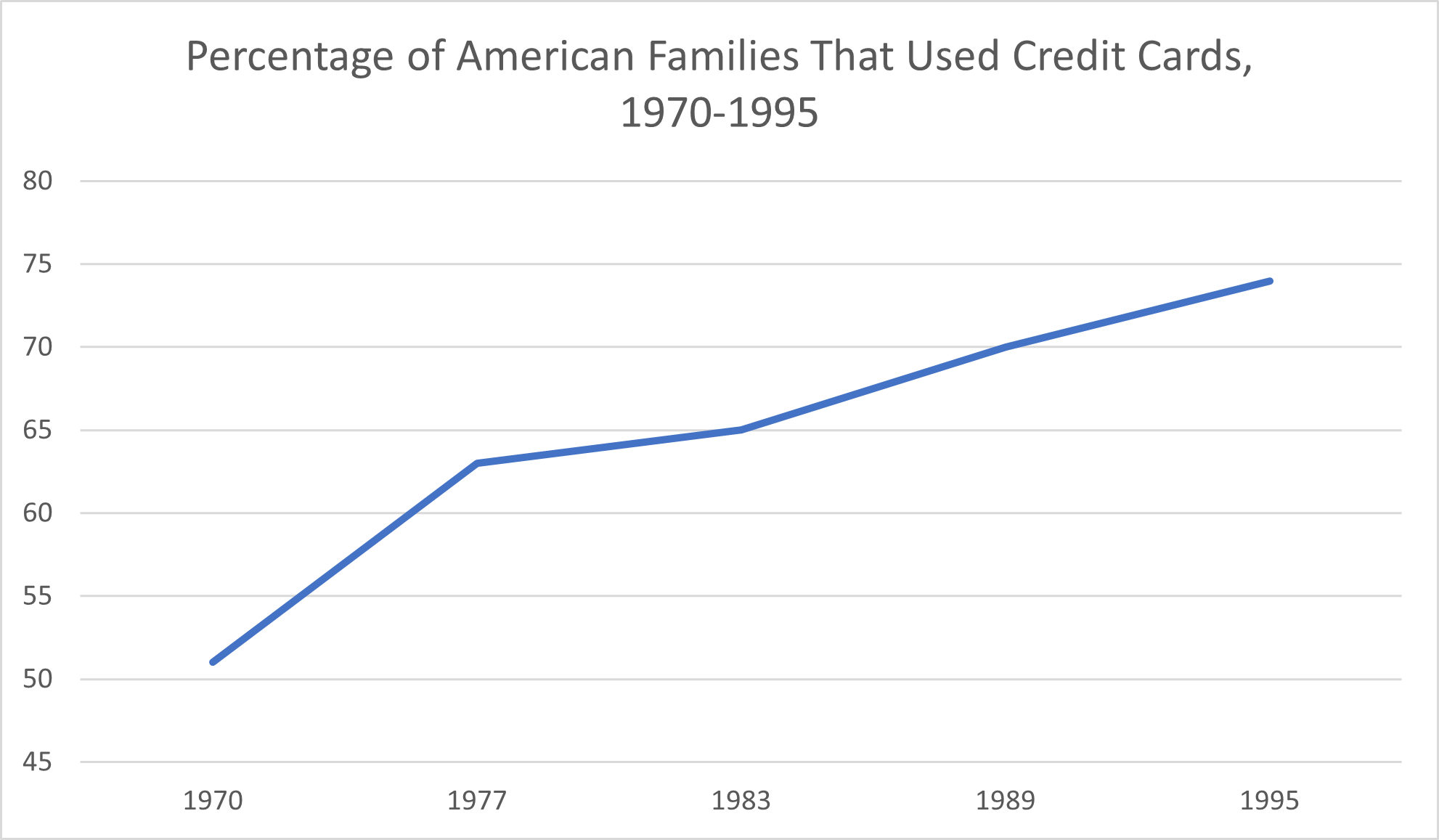

A September 2000 Federal Reserve Bulletin shows the growth in the percentage of U.S. households with credit card accounts between 1970 and 2000.

In 1970, just over half of American families reported having some sort of credit card. By 1977, that proportion had increased by more than 20%, with 63% of families now reporting ownership of a credit card. More modest growth occurred between 1977 and 1983, when credit card ownership rates amounted to 65%. By 1989, seven out of 10 American families had a credit card. In 1995, nearly three-quarters of families owned a credit card.

All in all, the increase in the percentage of American families that owned at least one credit card between 1970 and 1995 amounted to nearly 50%.

Credit Card Accounts and Users Today

Despite a slight drop-off in credit card ownership in the late ’90s—from 74% in 1995 to 73% in 1998—credit card accounts are more prevalent now than ever before.

In a 2022 FEDS Notes report published by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Reserve reported that upwards of 75 percent of households in 2019 had a credit card in their possession.

Among this majority of American households that own credit cards, more adults have a credit card, and cardholders tend to have more accounts, as well. A 2020 report by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System determined that 83% of American adults own at least one credit card. More than one-third of the American adult population reported having at least three credit cards, and the average number of credit cards per adult in the United States is 3.8, according to the job search website Zippia.

The massive increase in both the number of credit cardholders since the 1970s and the number of credit cards per American adult in recent years helps explain the growth of the credit card industry from the beginning of its existence through today.

How Much Is the Credit Card Industry Worth?

To get a better understanding of the consumer credit card market, it makes sense to look at changes in market size over time. In particular, we’re going to dig into the credit card issuing market size. A credit card issuer is the lender that provides the line of credit and takes on the funding costs and risks. Many issuers of credit card products are financial institutions, such as a bank or credit unions.

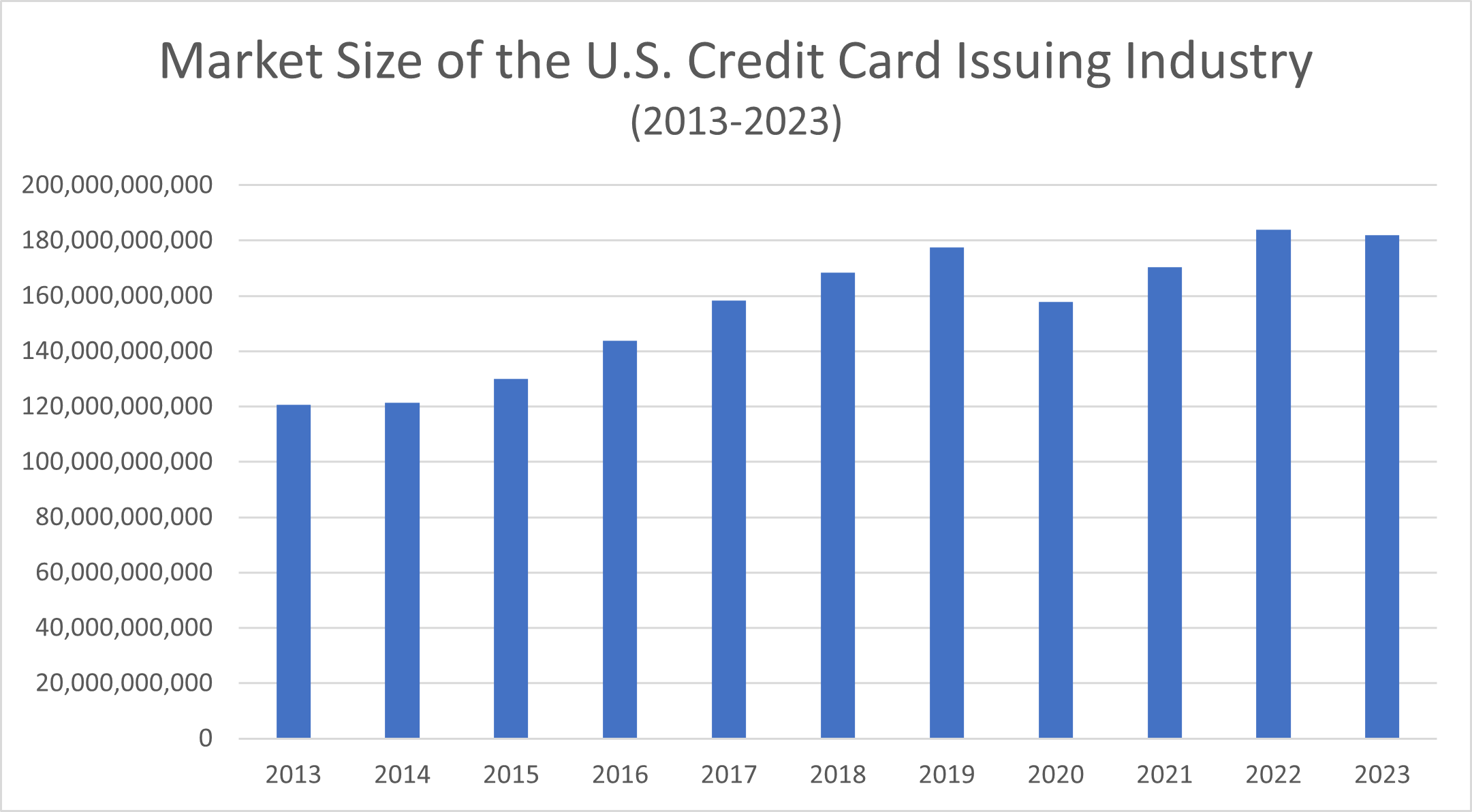

Industry market database IBISWorld records credit card issuing industry market size data specific to the United States market over the past decade.

In 2013, the issuing side of the U.S. credit card market amounted to $120,589,200,000. A modest increase to $121,322,800,000 in 2014 was followed by a larger jump to $129,965,200,000 in 2015.

For years, the revenue of the issuing side of the U.S. credit card business kept climbing. In 2016, the credit card issuing industry made $143,782,300,000. By 2017, the industry had seen a nearly $15 billion boost and was worth $158,236,600,000. Over the next year, revenues climbed by another $10 billion, leaving 2018’s U.S. credit card issuing market size at $168,297,300,000.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on the economy contributed to the sharp decline between the $177,559,600,000 credit card issuing market size reported for 2019 and the lackluster $157,812,100,000 market size in 2020. Fortunately for the credit card market, though, it didn’t take long for revenues to bounce back to pre-pandemic levels. 2021 brought a market size of $170,406,500,000. By 2022, the market size was at an all-time high of $183,875,300,000.

Despite the downward trends of 2020 and a slight (1%) projected decline in market size that puts the predicted market size for 2023 at $181,959,300,000, the overall average growth in market size between 2018 and 2023 amounts to 1.6% per year, IBISWorld reported.

These massive, hundred-billion-dollar figures may be hard to wrap one’s head around, especially without the context of how the size and growth of this industry compare to other industries in the United States. The credit card issuing industry has experienced slower growth rates over the past five years than the finance and insurance sector as a whole or the U.S. economy overall, IBISWorld reported. Still, credit card issuers rank as the 16th largest industry in the finance and insurance segment of the United States economy and the 79th largest market in the U.S. economy as a whole.

Credit Card Profitability

Market size is measured by total revenue, not profits specifically. The large (and, for the most part, growing) market size doesn’t directly address the question of how profitable credit card companies are.

The credit card industry processes a massive amount of money in transactions—amounting to $49 trillion in 2021 and representing years’ worth of double-digit growth rates, McKinsey & Company reported. However, the revenue that passes through the credit card industry when consumers make credit card payments isn’t pure profit for any of the players involved. Due to a variety of factors, credit card profitability rates are very different from credit card transaction volumes.

Factors That Affect the Profitability of Credit Card Companies

Calculating profitability means factoring in all of the expenses involved in a credit card issuer’s credit operations.

Banks and financial institutions have to contend with credit card industry issues that affect credit card profitability, such as the following:

- Operating costs

- The risk that the money lent to consumers in the form of lines of credit won’t be repaid

- Interest expenses that increase funding costs and eat away at banks’ profit margins

Fees (both transaction fees charged to vendors and consumer fees charged to account holders) and interest charges make up most of the credit card industry’s profits, NerdWallet reported.

The transaction fees (payment processing, assessment and interchange fees) account for only a comparably small percentage of the total credit card transaction volume. Then there are the consumer fees and interest charges. All told, American consumers paid a combined total of $120 billion (on average) in credit card interest and fees every year from 2018 through 2020, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau reported in 2022.

Credit Card Companies’ Return on Assets Rates

How do we assess the profitability of credit card issuers if total revenue only tells us so much about the market? We need to look at rates of return on assets reported by credit card companies.

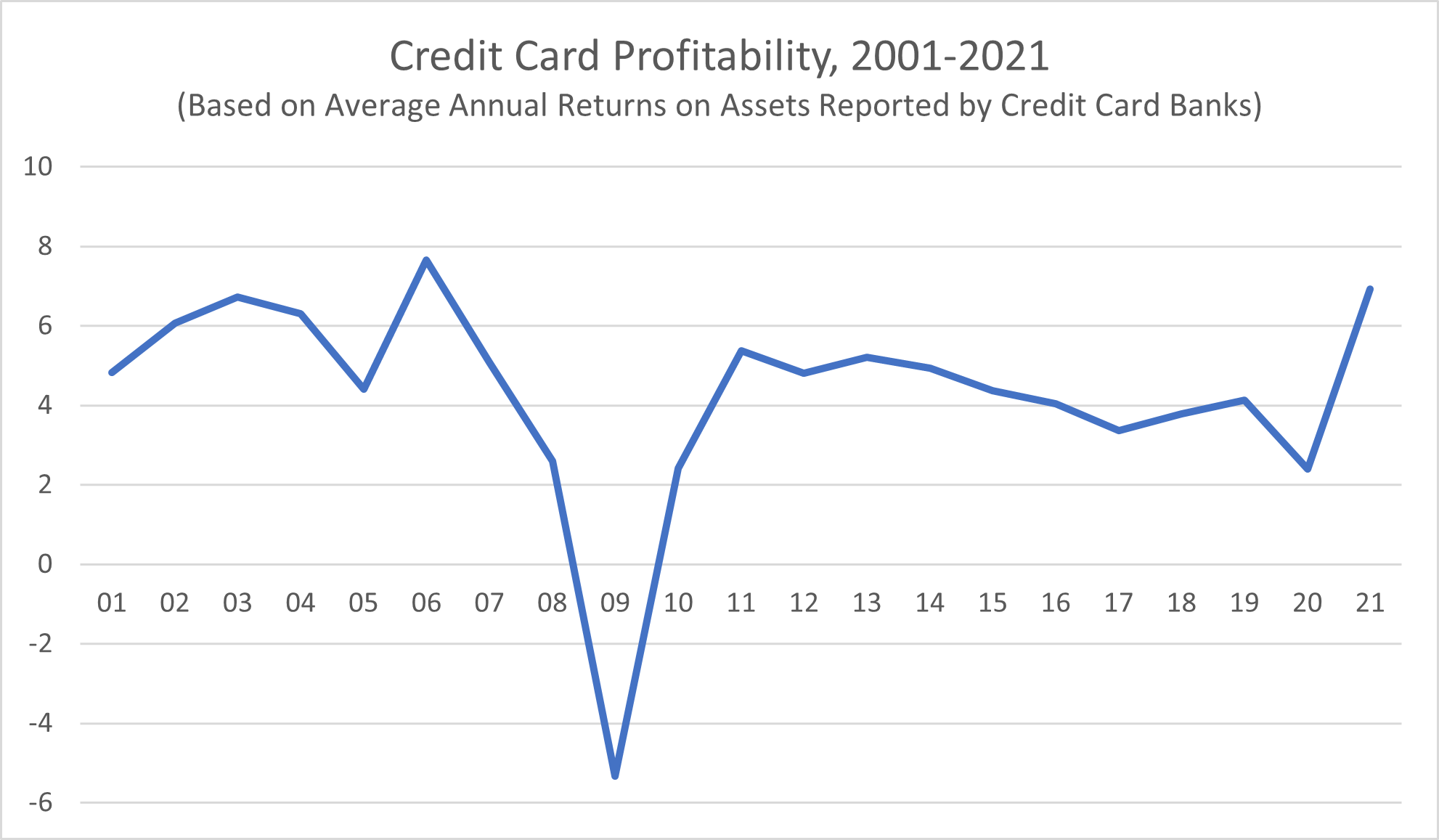

In its 2022 Report to Congress on the Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions, the Federal Reserve reported on the annualized return on assets reported by large U.S. credit card banks between 2001 and 2021. The Profitability of Credit Card Operations annual report shows how the returns on assets these depository institutions have reported have fluctuated over this two-decade period.

The highest annualized return on assets occurred in 2006, with a peak rate of 7.65%. The lowest annualized return on assets sunk to -5.33% in 2009. Since the mid-2010s, the annualized return on assets amount has been up and down, dropping from 5.20% in 2013 to 4.04% in 2016 before remaining in the range of 3% during 2017 and 2018. A brief increase to 4.14% in 2019 gave way to a 10-year low of 2.40% in 2020. In 2021, credit card banks reported an annualized return rate of 6.93%. In other words, credit card profitability in 2021 was the highest it had been in 15 years.

How Income Amounts and Funding Costs Differ for Credit Card Banks vs. Commercial Banks as a Whole

This differentiation between income (revenue) and profits applies to all financial institutions, not only credit card banks. How do income amounts and expenses differ between credit card issuers and commercial banks as a whole?

Credit card banks report considerably higher interest and noninterest income than all commercial banks, according to the Federal Reserve. In 2021, total interest income for all commercial banks amounted to 2.48% of average quarterly assets, while for credit card banks specifically, interest income reached 10.36%. Noninterest income amounted to 1.31% of average quarterly assets for all commercial banks but 5.62% for credit card banks.

The average interest and noninterest income rates speak to credit card profitability, but they don’t tell the whole story. For a business to be profitable, it must bring in revenues that exceed its expenses. It’s worth noting that, in spite of the higher income rates credit card banks report compared to all banks, expenses were also higher for credit card companies than for all commercial banks.

Interest expenses for credit card banks were more than five times those reported for all commercial banks. Noninterest expenses for credit card banks were more than three times the noninterest expenses amount reported for all commercial banks.

McKinsey & Company reported an overall return on assets for the credit card industry of 3.6% in 2020 and, based on this figure, called credit cards “one of the best-performing businesses in financial services.”

Credit Card Interest Rates Over Time

Could any discussion of how the credit card industry has grown over time be complete without looking at how interest rates have changed (and, especially, grown) over the years?

The interest rate is the percentage of the account balance or loan amount that the lender charges the borrower (or cardholder) for the privilege of borrowing the money. Interest rates vary from one credit card account to another. The higher the interest rate, the more the cardholder is paying on any revolving debt they carry from one statement period to another.

Interest rates on credit cards aren’t static. The average interest rate charged to credit cardholders changes over time due to factors like economic conditions, inflation, demand for consumer lending, and an applicant’s individual level of riskiness.

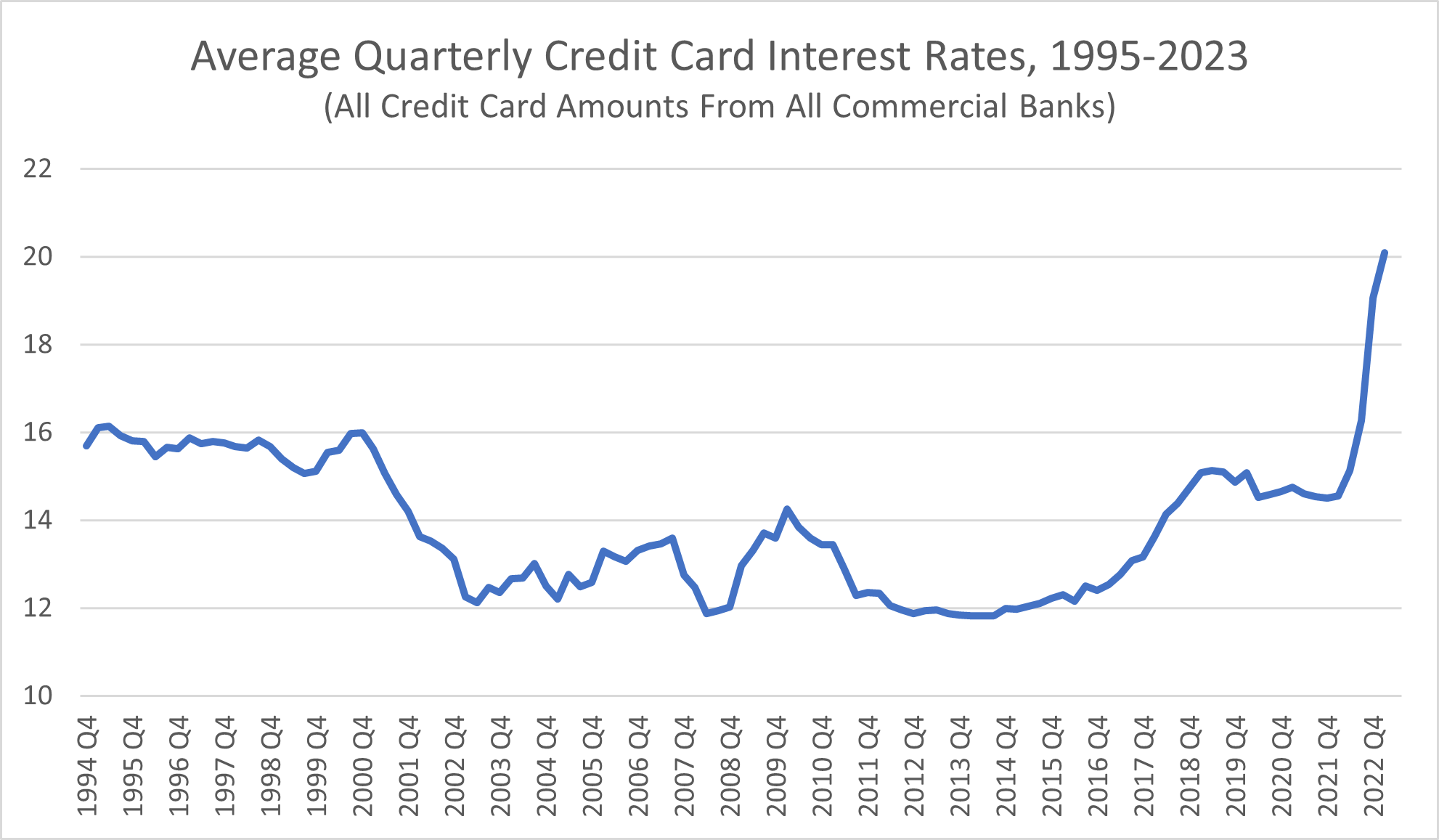

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System records average commercial bank credit card interest rates dating back to 1994.

The average commercial bank interest rate for all credit card amounts in the fourth quarter of 1994 was 15.69%. Credit card interest rates rose for a couple of quarters, peaking at 16.14% in the second quarter of 1995, before sliding back down into the 15% range, where they would remain throughout the rest of the 1990s.

Despite average credit card interest rates approaching 16% in the second half of 2000—at 15.98% in the third quarter and 15.99% in the fourth quarter—credit card interest rates would soon go in the opposite direction. By the third quarter of 2001, the average credit card interest rate declined to 14.59%.

Interest rates continued to fall through the early 2000s, first to the 13% range in early 2002 and then, in the first quarter of 2003, to the 12% range. Aside from a brief increase to 13.02% in the third quarter of 2004, average interest rates for all credit card amounts would remain in the 12% range until 2006, when the first-quarter average interest rate rose to 13.30.

Nearly two years of average credit card interest rates in the 13% range would give way to lower interest rates—amounting to 12.75%—by the close of 2007. From there, credit card interest rates would decline to a low of 11.88% in the second quarter of 2008 before climbing back into the 13% range to finish off the decade.

The first quarter of 2010 saw the average credit card interest rate exceed 14% for the first time in almost a decade, but the interest rate decreased from there to the 13% range in the second quarter of 2010 and then the 12% range by the second quarter of 2011. The third quarter of 2012 would see average credit card interest rates fall to the 11% range, where they would remain until the second quarter of 2015.

Credit card interest rates in the 12% range would persist through the second half of 2017. From there, credit card interest rates would grow from 13.08% in the third quarter of 2017 to 14.14% in the second quarter of 2018 and 15.06% in the first quarter of 2019. With the exception of 2019’s fourth-quarter average interest rate of 14.87%, credit card interest rates would remain in the 15% range for the remainder of the decade.

2020 began with an average credit card interest rate of 15.09%, but for the next several quarters, the average credit card rates hovered in the range of 14%. Interest rates began rising more sharply in the second half of 2022. The third quarter of 2022 saw the average commercial bank interest rates for all credit card amounts climb to 16.27%, exceeding 16% for the first time since 1995. By the fourth quarter of 2022, the average interest rate hit 19.07%, a marked increase not only from the previous quarter but also from the previous all-time high (16.14% in the second quarter of 1995). In the first quarter of 2023, the Federal Reserve reported, the average interest rate for all credit card amounts had climbed to 20.09%.

Despite periods of ups and downs throughout the decades, the 20.09% average credit card interest rate reported for the first quarter of 2023 is more than 25% higher than the 15.69% rate reported in 1994. That’s a substantial increase. It means that, on average, cardholders who carry a revolving balance are paying much more in interest charges today than they were on the same balance almost 30 years ago.

The increase in the average interest rate didn’t develop exclusively due to credit card companies charging higher interest rates on newly opened cardholder accounts. Interest rate hikes applied to existing cardholders’ accounts have played a significant role in the increase in average interest rates over time.

Cardholders often ask questions like, “Can credit card companies increase your interest rate?” Legally, yes, they can. In most cases, credit card companies can’t raise your interest rate on existing balances but can impose interest rate hikes that will apply to new balances, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau reported. A bank must typically give credit card users at least 45 days’ notice of rate increases.

Increases in Credit Card Balances Over Time

As you might suspect, the increases in credit card accounts across the United States over time have also led to an increase in total outstanding consumer credit balances in America. The higher the interest rate, the higher the amount of interest charges being piled onto the principal. Over time, the balance creeps up.

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System keeps a record of outstanding consumer credit each month dating back to January 0f 1943. Although this data encompasses all consumer credit debt from major types of credit, not strictly credit card debt, it shows how balances on consumer loans (including credit card balances) have climbed over the past 80 years.

The level of outstanding consumer credit in the United States in January 1943 amounted to $6,577,830,000 and declined throughout the year, ending at $5,462,520,000 in December. Not until November of 1945 would consumers again reach an outstanding credit balance above $6,000,000,000. After that, though, total consumer credit debt climbed rapidly—surpassing $7,000,000,000 by March 1946, $8,000,000,000 by August 1946, and $9,000,000,000 by November 1946.

Soon enough, American consumer credit debt would exceed $10,000,000,000 (in February 1947) and then $15,000,000,000 (in July 1948). The ‘40s would end with a total American consumer credit balance of $18,772,210,000. By the mid-1950s, this figure would double. Americans held a collective $56,010,680,000 in consumer credit debt by December 1959. Again, consumer credit debt levels doubled in a relatively short span of time, exceeding $100,000,000,000 by the time July 1966 rolled around.

The 1970s began with a January total outstanding consumer credit level of $127,802,990,000. The collective consumer credit balance in America would climb to $199,316,800,000 by August 1974 but then stall just shy of the $200 billion mark. Ups and downs—as low as $196,043,360,000 in June 1975—would follow until October 1975, when the total consumer credit balance finally surpassed $200,000,000,000. As the 1970s drew to a close, the collective American outstanding consumer credit balance rose to $348,589,410,000.

The 1980s saw total consumer credit balances more than double, from $350,056,230,000 in January of 1980 to $794,612,180,000 in December of 1989. Consumer credit balances climbed into the $800,000,000,000 range early in the 1990s before dipping back down into the high $700,000,000,000 range through late 1991 and early 1992. Growth in the mid- to late-1990s became more sustained. Outstanding U.S. consumer credit reached the level of $900,989,530,000 in April 1994, climbing to $1,010,395,040,000 in January 1995 and then $1,201,634,970,000 by September 1997. As the decade ended, Americans carried an outstanding consumer credit balance of $1,531,105,960,000.

After starting off with a total level of outstanding consumer credit debt of $1,538,520,180,000, the 2000s saw collective balances increase by $1 trillion. The outstanding balance in June 2005 amounted to $2,247,833,430,000, and by December 2007, it had grown to $2,609,476,530,000. Consumer credit balances would hover in the range of $2,600,000,000,000 for the next year and a half but would decrease to the $2,500,000,000,000 range by the middle of 2009. The decade would end with a collective consumer credit balance of $2,555,016,640,000.

With the Great Recession in the rearview mirror, the 2010s began to see outstanding consumer credit debt levels climb again. The balance reached $2,683,971,000,000 in May 2011, $3,000,137,610,000 in June 2013, and $3,420,426,570,000 in June 2015. By December 2019, American consumers carried a collective credit balance of $4,192,191,330,000.

Through the start of the 2020s, influenced by concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic, total outstanding consumer credit balances dipped from the January 2020 level of $4,207,664,020,000 to $4,184,852,540,000 in December 2020. From there, consumer debt has climbed—to $4,331,529,460,000 in August 2021, $4,445,523,750,000 in January 2022, and $4,785,809,190,000 in December 2022. The most recent data available, for February 2023, shows a collective outstanding American consumer credit level of $4,820,565,580,000.

Over time, revolving debt—debt carried from month to month, as credit cards today permit, instead of being paid off at the end of a statement period—has grown to make up a substantial proportion of all outstanding consumer credit debt. When the Federal Reserve first recorded revolving credit balances in 1968, only about 2.2% of the total outstanding consumer credit balance was in the form of revolving debt. Over time, that figure skyrocketed, peaking at around 40.5% of all consumer credit debt in September 1997. Although revolving debt as a percentage of all outstanding American consumer credit debt has declined, it still accounted for around 25% of the total outstanding credit balance at the end of 2022.

More revolving debt for consumers equates to more money paid to banks and credit card companies in interest. Over months, these added costs can really pile up, making the once daunting task of paying down credit card balances even more of a challenge for many consumers.

Credit Card Account Delinquency Over the Last 30 Years

If consumers don’t pay their credit card balances in full at the end of the statement period, they carry a revolving balance on which they must pay interest. What happens when they fail to pay their credit card bills at all?

Payments that are more than 30 days past their due date are considered delinquent. Delinquency is one of the key risks credit card companies take on when lending money in the form of credit cards. For consumers, credit card delinquency can lead to numerous negative consequences, including a decrease in credit score, closure of existing credit accounts, bills going into collections, and even lawsuits.

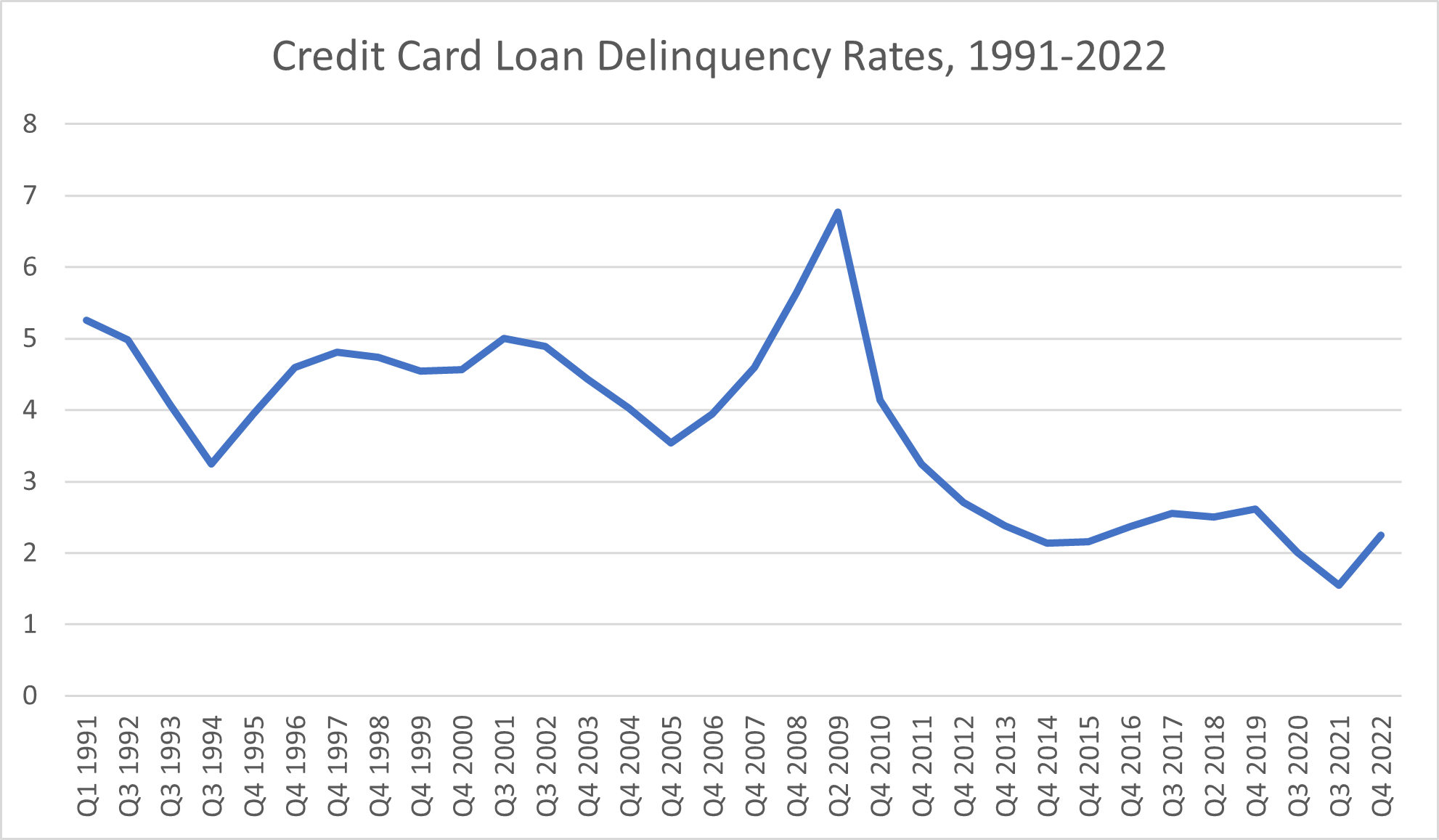

The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis records delinquency data dating back to 1991, which started with a 5.26% rate of delinquency for the first quarter. In 1994, delinquency rates dropped to 3.25%, which would be the lowest rates seen for the next 17 years. Delinquency rates exceeded 6% during the Great Recession, peaking at 6.77% in the second quarter of 2009, before dropping. Just a couple of years into the 2010s, delinquency rates would dip below 3%. 2020 kicked off another decline, during which (in the third quarter of 2021) the delinquency rate slipped to just 1.55%. Credit card delinquency rates at the close of 2022 were still lower than they had been even decades earlier, but by this time, they had again surpassed 2%.

While the data shows ups and downs in delinquency rates—including a drastic increase in credit card delinquency that coincided with the Great Recession—delinquency rates since the mid-2010s have been significantly lower than they were 20 years previously. Pandemic-related factors led to an all-time low in credit card delinquency in 2021, after which—as credit card spending began to return to pre-pandemic levels—delinquency rates began to climb.

Average Credit Scores Over Time

Looking at the growth of the total consumer credit debt and the average credit card interest rate may seem to paint a bleak picture for American cardholders. Even the delinquency rate is once again on the rise, despite the recent record lows. Are American consumers doomed to a life of debt?

The data isn’t all bad. One of the most promising credit card industry statistics in recent years is the average credit score in America. Comparing the average credit card debt in the state with the biggest debt compared to the state with the lowest credit debt.

Credit scores are mathematical calculations that predict the likelihood of potential customers paying back their loans. Lenders of all kinds, not only banks that issue credit cards, use credit scores to determine the level of risk associated with lending money to an individual consumer. Credit scores are intended to help prevent or at least reduce unfair discrimination in consumer lending, in compliance with regulations like the Fair Credit Billing Act of 1974 and the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009.

Based on potential borrowers’ or account holders’ credit scores, a bank will decide whether it will offer credit cards to applicants in the first place and, if so, under what terms the bank will offer credit cards. Credit limits and interest rates are among the terms which a bank issuing credit cards may adjust based on applicants’ credit scores.

The better (higher) an applicant’s credit score, the less risky the loan is for the bank—and the more likely the bank is to offer credit cards with higher spending limits, lower interest rates, and various other perks. The higher the average credit score among adults in the U.S., the better for American consumers.

Experian, one of the major consumer credit reporting companies used in the U.S., records average credit scores dating back to 2010.

The 689 average credit score reported for 2010 fits squarely into the “good” category—as do the average credit scores from every subsequent year recorded so far. On the whole, though, the average credit score in America is on the rise. It first exceeded 690 in 2012, coming in at 693 before dipping to 691 in 2013. By 2015, the average credit score had reached 695. In 2016 and 2017, the average credit score held steady at 699.

The average credit score in America broke the 700 threshold in 2018, amounting to 701, and it kept on climbing. In 2019, Americans’ average credit score was 703. 2020 would see the largest jump in the average credit score in a single year, with an 8-point increase that put the average credit score at 711. In 2021, the average credit score in the United States rose to 714, where it remained for 2022. Despite plateauing here, CNBC called this average credit score an “all-time high.”

All told, Americans are reporting better credit scores now than they were a decade ago. There were statistically meaningful increases in the percentage of Americans with scores in the highest categories of credit scores (indicating good, very good, and exceptional credit) and decreases in the percentage of Americans with scores in the lowest categories (650 and below) in 2022 compared to 2012, CNBC reported.

The Future of the Credit Card Industry

We’ve come a long way since the first plastic credit card and an even longer way since the single-store charge plates that gained popularity less than a century ago.

Could Biggins, who created the Charg-It card in the 1940s, and McNamara, who invented the Diners Club charge card in 1950, have ever imagined a world where the vast majority of Americans carry multiple cards in their wallet? What about a world where digital wallets, like the Apple Pay app, allow for credit card payments with a mere flash of a phone screen?

Credit Cards and Technology

The growth of credit card technology over the years has accomplished more than making it possible to pay by credit card. Credit card technology like EMV chips has put into place measures to reduce the risk of credit card fraud, a problem that basically dates back to the birth of the credit card industry.

Another major impact of developments in credit card technology has been improvements in the convenience of being able to pay by credit card. Today, contactless credit cards allow for faster, easier payments. You can wave contactless credit cards over a sensor or tap them against a card reader—no swiping, sliding, or inserting required.

Thanks to mobile payment services like Apple Pay and Google Wallet, you don’t even have to have your credit cards physically on your person to pay with credit. Instead, you can just scan your phone to charge purchases to your credit cards.

Outside of improvements to the existing methods through which technology has already made it more convenient and secure to pay with credit cards, it may be difficult to imagine what further technological advances in the credit card industry can accomplish from a consumer perspective. There are, however, many possibilities for banks to apply evolving technological innovations to credit card operations. Forbes points to artificial intelligence as part of the future of credit card technology—through aspects like determining whether to offer a line of credit and identifying fraudulent purchases—as well as part of changes in related aspects of the larger economy, such as how goods are marketed.

Keeping Credit Card Lending in Demand

The future of credit cards doesn’t refer strictly to technology, or at least to how technology is used to process transactions. A huge part of keeping credit cards as prevalent in the economy of the future as they are in the current economy is continuing to appeal to consumers.

Although most Americans have a credit card, not everyone likes using them. Reluctant credit card users may include seasoned cardholders who have racked up considerable credit card debt in the past and young consumers who find credit cards intimidating or even, in a financial sense, dangerous. Even consumers with no particular opposition to credit cards may prefer to use other methods of payment if those methods become more convenient or rewarding than a traditional credit card.

When will credit cards become obsolete? The answer may depend on how good a job credit card companies do appealing to potential customers and fostering consumer engagement.

As more consumers embrace mobile payment options like Apple Pay and Google Wallet, the physical cards themselves may eventually become less necessary. However, what’s most valuable about credit cards isn’t the actual card itself but rather the possibilities the line of credit offers consumers.

Credit cards make transactions more convenient because you aren’t limited in your purchasing power to the amount of cash you’re currently carrying. They allow you to purchase what you need now and pay for it later, even if doing so could cause you to incur interest charges. From the perspective of fraud, using credit cards is more secure than making purchases with cash, through which you can’t dispute a charge, or paying with a debit card, which if compromised can put at risk all the money in your bank account.

Competition is one of the biggest challenges facing credit card companies today and in the future. That competition isn’t solely from other banks and credit card networks, although competition within the credit card industry is a significant factor, too.

Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) platforms represent a new yet rapidly growing form of competition for traditional credit card companies, McKinsey & Company reported. According to survey data, McKinsey & Company reported, 39% of consumers who used Buy Now, Pay Later options for a transaction would have used a credit card if this option was not available to them, and 62% of BNPL users think that these platforms might eventually replace credit cards.

Failing to take seriously the threats BNPL platforms pose to the issuers of traditional credit cards would be a mistake. For credit card issuers to protect themselves from these threats, McKinsey & Company recommended thinking outside the box in which credit card issuing has historically situated itself.

Credit card companies that want to compete with BNPL platforms need to develop strategies based on consumer behavior. Facilitating consumer engagement by offering more than a mere payment method—for example, through loyalty programs, price-comparison tools, and discount-finding services—allows credit card companies to integrate themselves into the consumer’s “shopping journey,” McKinsey & Company reported.

Today’s consumers expect more from their bank than just another method of payment. For Americans with reasonably good credit, financing options are more abundant than ever. To stand out, the companies that issue credit cards and charge cards need to offer something more, like exclusive discounts, rewards that consumers actually want, next-level convenience, tools to enhance the shopping process, and other card benefits.

Embracing these expectations is one way credit card banks can keep ahold of their existing share of financial transactions in America and attract otherwise reluctant credit card users, even in the face of significant competition within and outside the traditional credit card industry.